MASTERPOST- All writing Toolkits

Three whole series of the Bruntwood Prize toolkit is up and available for you to use. Whether you are totally new to writing for the…

FOLLOWING HIS SMASH-HIT PRODUCTION OF TANIKA GUPTA’S ADAPTATION OF HOBSON’S CHOICE BY HAROLD BRIGHOUSE, ATRI BANERJEE RETURNS WITH A DEVASTATING NEW TAKE ON TENNESSEE WILLIAMS’ SEMI-AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL MASTERPIECE.

Tom escapes a suffocating home life through cigarettes and long visits to the movies while his sister, Laura, withdraws into her records and collection of glass animals. But their mother, Amanda, harbours dreams for them far beyond their shabby apartment. When Tom brings home a potential suitor for Laura, Amanda seizes the opportunity to change their fortunes.

THE GLASS MENAGERIE is a poetic and bruising portrayal of a family on the brink of change. Reimagined for the Exchange’s unique in-the-round theatre, this intimate and intense memory play explores the complex web of love, loyalty and trauma that binds families together.

A ROYAL EXCHANGE THEATRE PRODUCTION

2 SEPTEMBER 2022 – 8 OCTOBER 2022

https://www.royalexchange.co.uk/whats-on-and-tickets/the-glass-menagerie-2022

From 1902-08, the popular Austrian poet and novelist Rainer Maria Rilke corresponded regularly with Franz Xaver Kappus, a 19-year old officer cadet at a military academy in the south of Austria. Kappus was a fan of Rilke’s work, and had first reached out with a poem he had written.

Rilke, the son of an army officer, had studied at the academy’s lower school himself in the 1890s. Over this period, Kappus sought his advice on poetry in general; his own poetry’s quality; and in deciding between a literary career or a career as an officer in the Austro-Hungarian Army.

In 1929, three years after Rilke’s death from leukaemia, Kappus compiled these ten letters into a published edition he called “Letters to a Young Poet”.

Here’s my variation on the theme. E-mails, I guess, rather than letters.

“Nobody can advise you and help you, nobody. There is only one way. Go into yourself.”

Rilke, first letter to Kappus

Letter 1

Hello.

It’s so great to hear from you. Thanks so much for reaching out. I’m so pleased to hear about your play. Making art, any art, is an attempt towards changing the world, and after the last two years we’ve all had, god knows we need some change!

I think the weird, alchemical thing that happens between a play and a director is ephemeral and quite hard to pin down. And of course, as I’m sure you aware, very subjective depending on the play and depending on the director.

I can only offer some provocations, some thoughts, as to what, in my opinion, I might find exciting. These change from play to play, and from year to year, sometimes day to day. But I’ll try and write down some qualities that have felt pretty constant over the years. I really admire your bravery in putting pen to paper; it’s only fair that I repay that boldness with my own.

More soon.

Best wishes,

Atri x

Letter 2

Hi!

Here’s a short exercise for you. You might need a friend to help you. If they want to take part as well, all the better. The credit for this exercise goes to Ola Animashawun, a brilliant dramaturg, currently Associate at the National Theatre.

Here goes:

Two poems by way of inspiration, in case you find them useful. Two of my favourite poets, both American, separated by century but united in feeling.

Frank O’Hara, ‘Why I am not a painter’ (1957)

I am not a painter, I am a poet.

Why? I think I would rather be

a painter, but I am not. Well,

for instance, Mike Goldberg

is starting a painting. I drop in.

“Sit down and have a drink” he

says. I drink; we drink. I look

“You have SARDINES in it.”

“Yes, it needed something there.”

“Oh.” I go and the days go by

and I drop in again. The painting

is going on, and I go, and the days

go by. I drop in. The painting is

finished. “Where’s SARDINES?”

All that’s left is just

letters, “It was too much,” Mike says.

But me? One day I am thinking of

a color: orange. I write a line

about orange. Pretty soon it is a

whole page of words, not lines.

Then another page. There should be

so much more, not of orange, of

words, of how terrible orange is

and life. Days go by. It is even in

prose, I am a real poet. My poem

is finished and I haven’t mentioned

orange yet. It’s twelve poems, I call

it ORANGES. And one day in a gallery

I see Mike’s painting, called SARDINES.

Emily Dickinson, ‘Tell all the truth but tell it slant – (1263)’ (sometime between 1858-65)

Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —

With love,

A x

Letter 3

Hello! How was that? Painful? Painless? Hope you and your friend had fun.

Just to give you a little bit of context about the poems.

1)

“Why I am not a painter” is inspired by O’Hara’s visits to his friend Mike Goldberg, the Abstract Expressionist painter. In this poem, I think, O’Hara is grappling with various forms of creative expression. He suggests that the two modes — poetry and painting — have more similarities in them than difference, despite the title (ironically) suggesting otherwise.

O’Hara’s poem-in-the-poem is called ‘Orange’ and is inspired by the colour. His friend’s painting — when O’Hara first sees it — has the word ‘SARDINES’ in it. Later, he sees that that is all but gone from the finished picture: “all that’s left is just letters”. The painting, however, is now called ‘SARDINES’. O’Hara’s poetry cycle, in the same way, is called “ORANGES”, although the idea of ‘orange’ was merely the initial inspiration. Though the poet and the painter have been inspired by a particular word, neither word is immediately obvious in the finished work. Here’s Goldberg’s painting.

Sardines, Michael Goldberg, 1955, Smithsonian American Art Museum

I like to think of this poem whenever I think about directing a play. A play might seem to be about one thing, but really — beneath the layers of paint, or between the lines of verse — there is often something else entirely. Part of my job as a director is to connect to that initial nugget of inspiration; that initial heartbeat; the starting idea that breathed life into the whole play. If I’m excited by that, chances are I’ll be the right person to direct the play.

The poem also feels like a useful reference in thinking about plays as not being hermetically sealed in one art-form. Theatre can often feel quite rarefied. From the beginning of his career O’Hara — in his colloquial, humorous style — was interested in the meeting point between poetry and painting; music; dance. Although poetry can often feel quite exclusive too, I’m excited by the way that it has the potential to express ideas in vivid, condensed form. O’Hara’s style works for me as there’s something clear and un-pretentious about it. I hope you agree.

I’m always excited by plays that can draw, or at least allude to, other forms in order to reach their full creative expression. Phoebe Eclair-Powell’s play, SHED: Exploded View, which draws on Cornelia Parker is a good example of this. (You should check out Phoebe’s own blog on the play, which talks about form. It won the Bruntwood Prize last time round).

Jasmin Lee-Jones’ seven methods of killing kylie jenner is another good example, in the way it thinks about the Internet, and how we might represent that digital monolith on our stages and pages. Looking further back, Arthur Schnitzler’s Le Ronde, which take a round dance as its inspiration (think of children dancing when they sing “Ring a Ring o’Roses”).

It’s all about asking more from theatre than just existing behind a fourth wall, which can often feel safe and comfortable. It’s demanding it to speak to the here and now, a call to liveness (like Sami Ibrahim talks about here) and politically doesn’t allow theatre to get complacent, and exist merely for a privileged few.

A useful quotation to think about in this context is from a brilliant lecture by Omar Elerian, former Associate Director at the Bush Theatre. It’s called “Crashing the Gates: 5 Provocations on Contemporary British Theatre (2014)”

Describing the second iteration of Bush’s RADAR festival, he thinks about the form of new writing:

“While we spoke a lot about theatre and form last year – mainly in aesthetic terms – we thought we were missing the point by remaining confined within the insularity of the theatrical discourse, especially within the specific context of New Writing. So this year, we decided to open up the festival to a range of speakers, most of whom have very little to do with the theatre: architects, academics, musicians, campaigners, journalists, fashion designers. We asked ourselves: who defines culture today, and what are the experiences that will provoke us to think beyond the status quo? Who’s breaking the walls down, and who’s building the bridges from which we’ll acquire yet another vantage point?”

2)

I don’t have loads of context which I feel is necessary for the Emily Dickinson poem. The only thing I would suggest is that she’s asking something quite important about how we tell the truth: or and in other words, how we tell a story, and what that story’s relationship might be to the truth. Whether we need to tell it ‘slant’: sideways.

This becomes particularly important when we think about, as directors, our responsibility towards telling a story in a ‘truthful’ manner. Of course, this relates to whether we feel like we are the right person in terms of ethnicity, class, disability, etc… but more broadly whether we can take ownership over something that may feel deeply personal. Whether we have the capacity to express whatever that story might be, in a form that can hold it.

The act of directing is an act of care. The “name exercise” I gave you in the last letter is a way of articulating the way that story-telling is an act of care… what it means to be offered something personal — in this case, the story of a name — and to turn it into something artistic. In the case of directing a play, it’s about transmuting something that exists on the page so it can live on the stage. There’s a huge vulnerability in the relinquishing of a play, and all writers should be commended in their capacity to do so. It is the director’s responsibility to hold this with generosity and compassion.

I would never want to direct something that I didn’t feel like I could honour. However, if I can connect to the personal story at the heart of the play, then will no doubt excite me.

The (slightly backwards) lesson that this holds is that I would encourage you at all times to start with the truth. Although it may be dressed in layers of paint, or told slant, if there is truth at the core of your play it will resonate. It will be deeply and irrevocably felt.

You must, to some extent, define what truth means for you. But to invest in your truth is inevitably to cause someone else to be thrilled by it; someone who feels they can tell their truth, your truth meaningfully through the words you have committed to paper.

Much love,

A x

Letter 4.

Hello.

As a further example of what I mean when I talk about the truth of a play and how it intersects with my own truth, here’s a story about my grandfather. Here he is in Paris in 1973, the second from the left.

My grandfather was a man who grew up in British India, in Calcutta which was then the capital of the Raj. A kind gentle man, he was a professor of History. He had studied at Oxford and throughout his life, he wore trousers and shirts rather than dhoti panjabi; ate with fork and spoon rather than his hands, lived a life that, to all intents and purposes, tended towards the ways of the prevailing British ruling classes. A certificate from Queen Victoria still hangs on the wall of our family home today, given to his own grandfather in the 19th century.

A play I’ve admired since A-Level was William Shakespeare’s Othello. Studying it in sixth form drew me close to it on a purely textual level. More emotionally, I saw my grandfather in Othello’s character. Not in his tragic, murderous impulses, of course! But in his identification with the Venetians, despite being a Black man, a “Moor”.

In practically his first lines, Othello says to Iago:

Let him do his spite:

My services which I have done the signiory

Shall out-tongue his complains

The signiory — the parliament, as it were — will remember Othello’s loyalty. This focus carries on to his final speech. Just before his suicide, Othello reminds the assembled audience:

Soft you: a word or two before you go.

I have done the state some service, and they know’t.

No more of that. I pray you, in your letters,

When you shall these unlucky deeds realte,

Speak of me as I am…

Throughout the play, Othello is clinging on to his identity as solidified by professional service and an alignment with his ruling (colonial, arguably) masters. Othello is a tragedy, literally, of ‘disappointment’ – someone dis-appointed from his position. Stuck in Cyprus with no war to fight. It is this fragmented identity — this lack of ‘appointment’ — that Iago is able to exploit as the play goes on. This results in a fundamental fracturing of how Othello understand himself. What T. S. Eliot dismisses as “tragic self-dramatisation” is rather, for me, a desperate attempt by the man to hold on to his identity in the stripping winds of racial oppression and a deep, insidious pressure to assimilate.

As a brown man growing up in the UK these are all pressures I personally can identify with. And although the situation is of course far more extreme than that of my grandfather, the circumstances are not without their similarities. There’s something going on here that means that whenever I’m asking that fundamental question about whether I’m the right person to direct a play:

WHY ME?

I’m looking for something in the play’s truth that will resonate with my own. The story of my own name, as it were.

I’m not suggesting that one should bend one’s truth to fit someone else’s. Nor do I think that there is truly any way to predict what someone else might see in your truth, and in your play. Rather, I imagine that if you trust in the truth of it, something you might never have imagined might resonate for someone else.

Shakespeare might have never imagined my grandfather consciously. But in a way, though… he must have done.

A x

Letter 5.

Hi.

Hope you’re still with me. Here’s where it gets a bit wacky.

I’m excited by how plays resonate through the ages. How the boundary between Shakespeare/my grandfather is more porous than one might initially imagine.

I call this bit “finding the ghost”

“The thing about the past is that it’s not the past”

(old Irish saying)

“Perhaps the theater is a form of eulogy and our job is to raid the graveyard regularly. The ways in which we remember dead people, those who did not finish what they had to say, and the way that we give them voice is what matters. I like to think that if the theater were a verb, it would be “to remember.” We re-member the parts. We put the fragments back together again. We excavate history in order to allow the past and those who had not finished communicating speak through us in the present moment. We are flesh and sensation and we look to be filled with the spirits of ghosts. Can we vibrate with their energy and consciousness?”

These are the opening lines of a brilliant 2019 blog by Anne Bogart

In it, she speaks about the sacred form of theatre. How it stems from Japanese Noh theatre. She spends a decent amount of time on the Ghost of Hamlet’s father. His invocation to “remember him”… to put him back together, to avenge his unnatural murder.

When we talk about staging revivals we must hear the etymological resonance in the word itself – to re-vive, to live again.

The performance artist Dickie Beau created a show called Re-member Me which I saw at Contact a few years ago. The show saw him lip-syncing to various people who had performed Hamlet through the ages… eventually reaching Ian Charleson, who played Hamlet at the NT while dying of AIDS. We hear the voices of McKellen and others discussing Charleson – what he meant to them.

The show became, then, a memorial to Charleson as well as the countless individuals who lost their lives to the AIDS pandemic over the years.

https://twitter.com/DickieBeau/status/1431177032155766786?s=20

If we can imagine the stage-space in this memorialising way… if we can imagine theatre to have this sacred, almost mystical, shamanic energy… to think of a rehearsal as a seance, where Hamlet will be channelled, Othello channelled, Ian Charleson channelled… it allows us to understand the play as existing on a continuum.

In dialogue with all the other versions of the play, rather than necessarily as a fixed, singular thing.

An eternal dramaturgy, if you will.

Plays can be ghostly as well as live. The ghosts of 1605 thrum in 2022, and so on. As Bogart puts it: “We are attempting to communicate with spirits, to receive messages from ghosts”.

One of my favourite plays is Luigi Pirandello’s 1921 masterpiece, Six Characters in Search of an Author. During a rehearsal in a theatre in 1921 Rome, a group of ‘characters’ storm the stage, demanding that their story be put on as their author didn’t finish it. The director, after some persuasion, agrees – and the characters’ story takes over the theatre.

The only character who protests is the Mother of the two youngest Characters, the children. They — spoiler alert! — will die at the story’s climax. She doesn’t want to see the story staged as it means re-living her trauma over and over again. As she says at one point (in my own translation):

MOTHER

No, it’s happening now, it’s happening always! My torment isn’t finished, mister. I live every moment of it, and every moment of it is in me. Those two over there… have you ever heard them talk? They can’t talk, mister! All they do is keep my anguish alive: but they’re not there, they’re not there anymore!

It is a powerful metaphorical expression of the fact that when people live in trauma or in grief the feelings do not exist linearly, nor can they be expected to subside or abate over the course of time as we might expect: there are loops, waves, patterns that repeat themselves over and over again. This is inherent, I believe, in the form of a play; or a rehearsal process; or the run of a show, that happens night after night; or a classic that is staged year after year after year.

Oedipus will always gouge his eyes out. Hamlet will always question whether to be or not to be.

I’ll be directing The Glass Menagerie at the Royal Exchange later this year. In that play, our protagonist, Tom, channels Tennessee Williams himself. In Williams’ attempt to exorcise his guilt over his sister Rose Williams and her treatment for schizophrenia, we see Tom returning to his tenement block in St Louis, revisiting the story of his sister Laura and mother Amanda. An attempt to apologise for? forget? re-shape? the trauma of those years.

He will have done so at the play’s premiere in 1944. He will be doing it in Manchester in 2022. He’ll be doing it who knows where else in 2325. He persists beyond the play.

The ghosts persist. The play and the performance shape around them.

Atri x

Letter 6.

The final thing I would say to you is that if you are looking for the ghost, you are almost certainly looking for what makes the play eternal.

My favourite stage direction in The Glass Menagerie takes place when (sorry, spoiler alert again) we realise Jim, the Gentleman Caller, has a girlfriend called Betty already, and so won’t be marrying Laura in the end

AMANDA: Betty? Betty? Who’s – Betty?

(There is an ominous cracking sound in the sky.)

JIM: Oh, just a girl. The girl I go steady with!

(He smiles charmingly. The sky falls.)

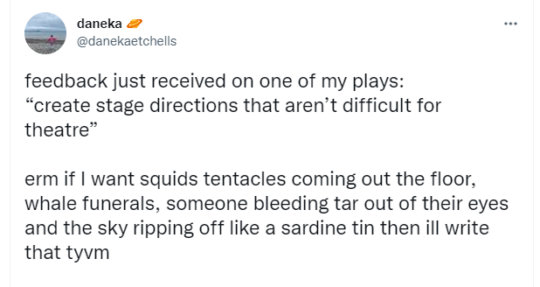

The sky falls! What a treat for any director. Other articles in this series have written eloquently about the value of “unstageable” stage directions : Sarah Kane’s sunflowers, for example.

A recent Tweet by the playwright Daneka Etchells also created some discourse on theatre Twitter last week:

https://twitter.com/danekaetchells/status/1517177842248859655?s=20&t=4jyAOcL5QUtQ150h6V6PDw

Stage directions like this are exciting because the invite us into the metaphorical, poetic world of the play. We are invited to understand the theatre as a symbolic space rather than a literal one; built on fragments, echoes, myths over time. There is a grasp towards apocalypse in this stage direction which I find thrilling. The domestic disappointment in this family can resonate on a cosmic scale.

A final exercise for you to consider. Credit for this goes to the brilliant director Lyndsey Turner:

See if you can distil your play into a sentence that starts “Once upon a time”. Rewrite it as a fairytale.

When I directed Phoebe Eclair Powell’s Harm at the Bush last year, this was a super-useful way in to the story. It’s a portrayal of a lonely woman, stalking a social media influencer who, soon in the story, turns out to be pregnant. I was excited by the language of animals, of the supernatural, of wildness within it.

“Once upon a time there was a lonely witch…”

It allowed the team and me to tap into a version of the play that felt less literally focussed on the Internet and rather something more archetypal, more mythic. Phoebe had built in several references to Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland into the play. These sorts of discoveries meant that, eventually, the singular prop we hand on stage was an over-sized stuffed bunny rabbit, which was eviscerated over the course of the play.

Kelly Gough in Harm, photo by Isha Shah

The fairytale at the heart of the play is not far away from the play’s ghost. They both unlock the play into a more subliminal, often a more emotive space. It doesn’t matter if the subject matter is grounded in reality: if you can unlock these archetypes — whether they’re from fairytales, from Greek mythology, from old Hindu folk stories, wherever you might find them — chances are you’re hitting on the seam of something universal.

Another stage direction I really love is from good old Shakespeare again. At the end of the masque in The Tempest, the “Nymphs” and “Reapers” “heavily vanish” – this, for me, epitomises the potential of what theatre can be. The lop-sided, pendulum-like “vanishing heavily” – how something can be ephemeral, but also exist in the concrete, present time… this epitomises, for me, the gorgeous paradoxes of what theatre and a play can hold.

Good luck, writer. I’ll leave you with these thoughts for now. Keep well and best wishes.

With love and care

Atri x

Atri Banerjee is a director based in London. He was recently named in The Stage 25 list of theatre-makers to look out for in 2022 and beyond. This year, his work will be seen across the UK in three different productions; earlier this spring, he directed Kes in a co-production between Octagon Theatre Bolton and Theatre by the Lake Keswick, and following Britannicus at the Lyric Hammersmith this summer, he will direct The Glass Menagerie at the Royal Exchange. In 2019, he won The Stage Debut Award for Best Director and was nominated for the UK Theatre Award for Best Director for his production of Hobson’s Choice at the Royal Exchange.

Atri trained at Birkbeck and on the National Theatre Directors’ Course. He was previously Trainee Director at the Royal Exchange and a Resident Director at the Almeida Theatre. He is a mentor for the JMK Trust and a Trustee of the Regional Theatre Young Directors’ Scheme. Other directing credits include Harm (Bush Theatre), ERROR ERROR ERROR (Marlowe Theatre/RSC), Hidden Fires and Name, Place, Animal, Thing (both Almeida), Europe (LAMDA) and Utopia (Royal Exchange). Film directing credits include Harm for the BBC Lights Up season on BBC Four with the Bush Theatre.

Assistant/Associate Director credits at the Royal Exchange include West Side Story, The Mysteries (also tour), Happy Days, The Almighty Sometimes, Jubilee (also Lyric Hammersmith) and Our Town. Other Assistant/Associate Director credits include The Nico Project (Manchester International Festival/Melbourne International Arts Festival) and The Son (Kiln Theatre).