REPOST- Bruntwood Prize Toolkit WEEK ONE- Getting Started

In a statement regarding COVID19 the Government has advised people to stay away from theatres. During this public health emergency, the safety and wellbeing of…

During this public health emergency, the safety and wellbeing of our staff, artists, audiences and families comes first.

We are exploring ways in which we can all remain connected and optimistic. The Bruntwood Prize has always been about much more than the winners. It is about opening up playwriting to anyone and everyone, to support anyone interested in playwriting to explore the unique power of creative expression. Therefore we want to make this website a resource now for anyone and everyone to explore theatre and plays and playwriting.

So we will be highlighting the many different resources archived on this website over the coming weeks.

Kendall Feaver won a Judges Award in 2015 for the brilliant ALMIGHTY SOMETIMES

Welcome to the fun part! Enjoy this part! This is where you get to dream, imagine, plan and play! Everything is in a wonderful state of possibility and you haven’t yet muddied it with terrible first draft writing! Whee! Now…let’s conjure some people.

Part One – Finding Characters

By this point, you will hopefully have a glimmer of something. It might be a fragment of story, an image, an interesting character voice, a situation, an issue or a question. Something that burns you up inside, confuses, horrifies or delights you. Something that has compelled you to think “…this could be a play…”

For my Bruntwood play, The Almighty Sometimes, my starting point was the recent and rapid increase in mental health diagnoses in young people. This might sound a bit inaccessible as a play idea (indeed, when I pitched this idea round, many people told me it was!) but anything can be play. Anything. The experience of watching your play just needs to be an interesting one (I’m a big fan of Anthony Nielson’s provocation, THOU SHALT NOT BORE) and one of the best ways to keep your audience engaged is to find that group of complex, vibrant, contrasting characters that will drive your story forward.

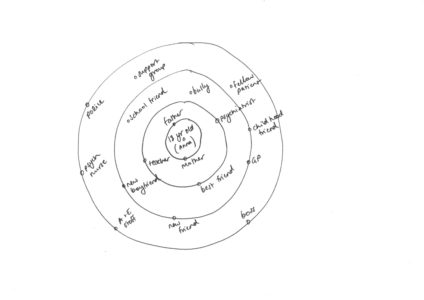

Exercise 1. Draw a series of concentric circles, a bit like a dartboard. The ‘bullseye’ or ‘epicentre’ is that ‘something’ compelling you to write this play. Now imagine all the possible people who exist in this world. Map them according to how far they exist from the epicentre.

My dartboard might have looked something like this (a bit rough, but you get the idea!)…

Exercise 2. Looking at your dartboard, think about which people interact with each other, where and under what circumstances, and how crucial they are to the story. Pick the characters that most interest you and note these rough details beside them, as well as anything else you may have realised while mapping them.

My notes might have looked something like this:

Eighteen-year-old (Anna) – on the epicentre, protagonist (?), will interact with all people on the dartboard, moves between domestic and clinical environments, but shouldn’t be away from these environments. Her world is routine and geographically small.

Mother (Renee) – interacts with all (another possible protagonist?), but things will get complicated if she engages with boyfriend or psychiatrist (!), will move between home and work, cannot visit psychiatrist without Anna’s permission.

Psychiatrist (Vivienne) – will interact with Anna at the office, never a domestic setting, but possibly hospital if it gets to that point. Really shouldn’t interact with mother or boyfriend without Anna’s permission.

New Boyfriend (Oliver) – interacts with Anna, possibly mother though this could get awkward (!), shouldn’t engage with psychiatrist. Will exist in Anna and Renee’s world, but perhaps they also come to his (?). Maybe he’s a link to a new setting for Anna, expands her world a bit?

Already you can see several dramatic possibilities beginning to form, many of which you will develop at a later stage. But at this early stage, you’re primarily looking for the minimum number of characters required to tell this story. This isn’t just a cynical attempt to get your play programmed (though if you’re an emerging writer, the smaller your cast, the higher the probability!) it will also help focus your story by condensing it down to its most crucial elements. Also, it’s worth remembering that actors will gravitate towards roles that allow them to showcase some degree of range and skill, and it’s difficult to write these complex roles if you dilute the action across too many characters. As you develop these characters, keep thinking to yourself, “Will someone want to play this part?”

Finally, remember the importance of a well-balanced cast: every character should provide something both unique and essential to the story. If at any point you’re worried about this, either rework the character or see if you can write the play without them.

Part Two – Creating a Character

Of course, characters aren’t just dots on a dartboard…they’re living breathing human beings, with complex interior worlds and a whole life that existed before the start of your play. This history is important and will influence how they behave and react in the present-day reality of your play. Every character will also have their own individual needs, wants and desires, which often (but not always) sit in opposition to the needs, wants and desires of everyone else.

Exercise 3. Get to know your characters by completing a quick character sketch (biography) for each. There are plenty of worksheet examples available online and/or spend a few hours answering Cheryl Martin’s fantastic character questions here.

There really aren’t any hard and fast rules as to what makes an interesting character, but here are a few suggestions…

Part Three – Giving your character a voice

Every character in your play, no matter how small the role, will have their own distinctive voice. This voice reflects who they are as people, but also needs to comply with the particular pressures of the scene and setting e.g. a teenager who swears in the presence of friends might not in the company of a teacher! There will always be little pieces of you, the author, in every character…just be careful their voices are not a perfect echo of your own.

Exercise 4. Looking over your character sketches, think about how background and personality traits might influence each character’s voice.

Try playing with rhythm, intonation, syntax, punctuation, choice of words and sentence length. Is your character’s vocabulary shaped by age, education or background? Do they speak in short, clipped sentences; long, convoluted ones; or do they mumble or mutter a lot? How does their voice change when they enjoy speaking to someone as opposed to not?

As a quick example, in The Almighty Sometimes, eighteen-year-old Anna is highly imaginative, quick thinking, intelligent, volatile and very self-involved. She uses long run-on sentences, her thoughts change rapidly, she peppers her speeches with big words, asks a lot of questions and usually cuts people off before they can give her a complete answer. In comparison, twenty-one-year-old Oliver is a more generous individual, but practical in his thinking and also quite reserved. Renee shares Oliver’s approach to the world, so the differences in dialogue are subtle, but their voices still reflect a difference in age, education, background and relationship to Anna, while acknowledging the pressures of the particular situation (Oliver is scared of heights; Renee is terrified that Anna will hurt herself).

|

ANNA: Not scared of heights then?

OLIVER: No, not really.

ANNA: Good. Because if you fell from here, you wouldn’t make it. Twenty feet is all it takes, did you know that? Anything above twenty and cat instincts are useless. I looked it up once, looked up how to survive if you fell from a plane, or if your parachute doesn’t open up, or if you slip from scaffolding attached to the side of a building, looked it up and you know what it said? “It is always best not to fall at all” That’s it! “It is always best not to fall at all.” What happens to the body, do you think? The physics of it, not the boring otherworldly stuff. What happens to a body when it falls, all the way, all the way to the ground, what happens to a body when it–

OLIVER: Rather not think about it, if I’m honest.

Beat.

ANNA: Sorry…am I doing that thing where I’m talking too much again? OLIVER: No, you’re fine– ANNA: Because I don’t have to talk. I mean, if you don’t want me to talk, I’m happy to just sit here, look at the view– OLIVER: No, I like listening to you– ANNA: Because it doesn’t really seem like it to be honest– OLIVER: No, I promise, I do – I’d just rather you talk about something that doesn’t involve like– ANNA: The total obliteration of a person– OLIVER: Yeah.

|

| ANNA: I have to go now.

RENEE: Anna–

ANNA: I have to go I have to go I have to go–

RENEE: Where?

ANNA: Where are my keys, where are my fucking keys?

RENEE: You don’t know how to drive.

ANNA: Then I’ll walk.

RENEE: Where to?

ANNA: HarperCollins, or or or the one in the bubble.

RENEE: I’m sorry?

ANNA: You know, supercalifragilisticexpialidocious, bow tie bow tie, fucking stupid animal–

RENEE: Penguin.

ANNA: Yes! I’ll go to Penguin! NO! HarperCollins. None of this paperback bullshit, would I be responsible for that do you think?

RENEE: Responsible for what?

ANNA: The number of trees it takes to, whole forests maybe–

RENEE: Anna–

ANNA: Because I want it to be read, Mother, you know I do, but if it means I’m liable for any unnatural disturbance then I just don’t think–

RENEE: ANNA.

ANNA: What?

Beat.

RENEE: I think you might need to slow down a bit, sweetheart.

ANNA: Slow down?

RENEE: Yes. ANNA: Slow down?!

|

Finally, remember that all of this prep work is in a constant state of flux: don’t beat yourself up over the details. Writing something down about your character doesn’t make it concrete, it’s just the key that unlocks your brain, gives you a practical task in the face of any fear or anxiety, and keeps the creative process moving. Over the next ten weeks, you will discover more about your characters as you write them – you might even go back to your dartboard and pick another character entirely – but the most important thing is to begin.

For more character inspiration, check out Anna Jordan’s earlier article here, and if you’d like some more homework this week, do try the exercises in Bryony Lavery’s 2015 Bruntwood Workshop on character.

Kendall won a Judges Award in the 2015 Bruntwood Prize for Playwriting. Her play, The Almighty Sometimes, enjoyed a critically acclaimed season at the Royal Exchange, Manchester, and went on to win ‘Best New Play’ at the 2018 UK Theatre Awards. Kendall received further nominations for ‘Best Writer’ at The Stage Debut Awards and ‘Best New Work’ at the Sydney Theatre Awards. Most recently, she was the recipient of the 2019 Victorian Premier’s Prize for Drama, part of Australia’s largest literary awards. Kendall has been invited on attachment at the National Theatre Studio and the Bush Theatre. She is currently under commission to Manhattan Theatre Club, New York, and Belvoir Theatre Company, Sydney, and is the 2019 Philip Parsons Fellow at Belvoir.

Comments

Add comment